The Transformational Gospel of Jesus #36: What does God do with jerks?

“My son” the father said, “you are always with me, and everything I have is yours. But we had to celebrate and be glad, because this brother of yours was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found.” Luke 15:31-32

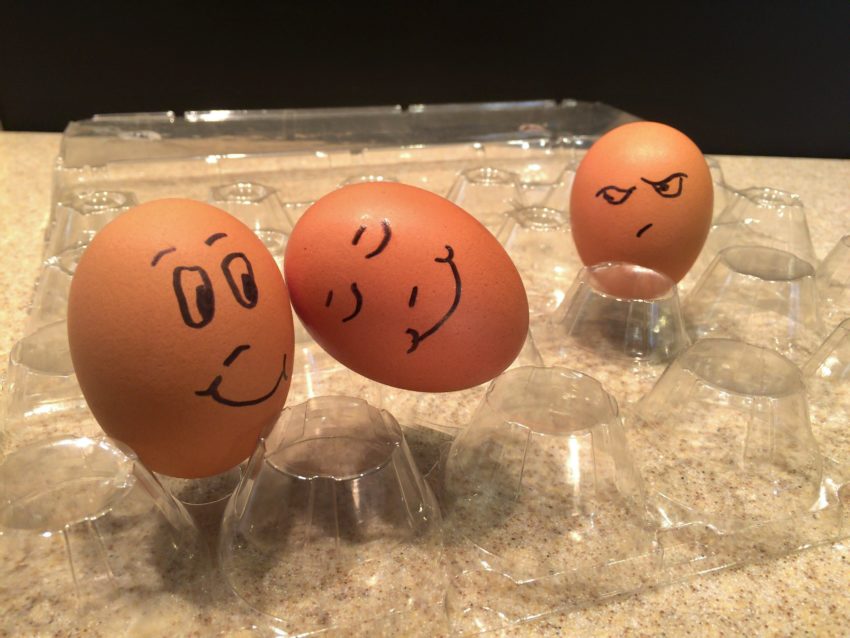

I have worked with many a prodigal over the years and what I have learned is that prodigals can be real jerks. They take what they think is theirs and waste it. They can be blind to the harm they cause. They often devalue the most important thing they have. They are offensive. They tick people off—on purpose. They leave a mess in their wake.

In probably one of the best-known stories that Jesus told, he starts with the shocking point that the younger son was not content to wait until his dad died in order to claim his inheritance. He demanded it upfront and then partied it away with his fair-weather friends. His disrespect for his dad was bad enough, but the implication was that he put himself in a place where, when the day came, he would not be able to fulfill his duty as a son to care for his aging father. He spent his way into the pigpen, finding himself, not his dad, being the one stressed by his insolence.

Because this story is often used to illustrate the idea of salvation, we can miss the cultural point. The son already belonged. As an Israelite, he was part of the covenantal people. He was not some outsider needing to get in. He was someone who had contemptuously turned his back on who he really was. But he never stopped being family.

This truth explains the father’s response. He has been waiting for his son’s return. He runs to meet him. He dresses him, puts a ring on his finger; throws a party for this prodigal who has stumbled home. Why? —Because his son belongs. As messed up as he knows he has been, the father restores him to his place with a headlong enthusiasm that distresses the one other character in the story—the older brother.

In reality, this was not a story about a lost son so much as it was about a brother who wanted his returning sibling to get lost. This prodigal had wasted his life. Why should he be loved as much as the one who had stayed the course and had done his duty?

If you read the story’s afterword, you, of course, know that the older brother represented the Pharisees. They were offended by this story because they got the point better than a lot of us do. They actually were the older brother, preening in their own goodness while disturbed by the messiness of other people’s lives. In their minds, how could the Father love ‘those people’?

I find this attitude still very evident in the church today. People blow up their lives. Their unfinished business gets out of hand. They cause conflict in the church. Their homes become battlegrounds. They become, in the words of Gordon MacDonald, VDPs—very draining persons. They take all they can and give nothing back. They devastate everyone they touch. In the eyes of the present day older brothers, throwing them under the bus is the best way to peace in the church. For them, it is inconceivable that ‘those people’ can even be restored.

Except that is precisely why Jesus is telling this tale. He came to transform people whom a lot of believers think are too great of a jerk to be salvaged. He does this because they belong to his family. And Jesus transformed these jerks in the face of skepticism and resentment. His transforming work is not up to the approval of the leadership team, nor the consent of those who have been disturbed by the antics of the prodigal.

The transforming work of the gospel, because of its inclusiveness, confronts our attitudes. Will we be glad that people who were jerks are being restored to serve and worship alongside us or will we be the jerks who are glad when they are gone? Whatever we choose will either open us up to loving prodigals on their transformational journey or standing in need of transformation ourselves.

-Steve Smith